You’ve Been Wrong About ’70s Rock This Whole Time — Here’s Why

Led Zeppelin for Celebration Day - Led Zeppelin / YouTube

The 1970s often get flattened into a single cultural punchline — a swirl of disco balls, mirrored floors, and sequined outfits. It’s easy to package eras into tidy stereotypes, but real trends never move in straight lines. Music especially shifts in waves, bleeding across years and borrowing from what came before. While pop culture loves the idea that the ‘70s were defined by disco alone, the decade’s heartbeat told a different story.

Strip away the hindsight bias and the caricatures, and a clearer picture appears. Rock was not hiding in some smoky underground club. It dominated radio, arenas, and album charts. The biggest voices of the decade weren’t only the falsettos of the Bee Gees or the nightlife glamour of “Saturday Night Fever.” The true backbone of the ’70s belonged to musicians pushing amps to their limits and audiences who filled stadiums to hear them.

Look at the era without shortcuts and the misconception falls apart. Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Eagles, Queen, Aerosmith, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Deep Purple, and dozens more led the commercial charge. Seven of the decade’s ten best-selling albums were rock records. The remaining two film-soundtrack outliers rode the late-decade disco wave — proving more how strong that wave needed to be to briefly interrupt rock’s near-total hold on the decade.

Counterculture Becomes the New Mainstream

By the time the ’70s arrived, the countercultural explosion of the late ’60s had already reshaped Western culture. The social upheavals tied to civil rights, war resistance, gender openness, and freer artistic expression were tightly intertwined with the era’s music. The artists who defined those years — The Who, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, the Rolling Stones — weren’t fringe voices. They were shaping the direction of popular taste while still carrying the rebellious spirit that launched the movement.

The turning point was 1969’s Woodstock. The festival didn’t just close a chapter of the ’60s; it signaled the start of rock’s most powerful commercial era. Suddenly, the sound once labeled “youth culture” was the dominant culture, supported by major labels, national tours, and an audience that stretched from suburban teens to university crowds to working-class listeners across the U.S., Canada, and Europe. When the decade turned, rock wasn’t competing with pop — it was pop.

The early ’70s album landscape proved it. Black Sabbath carved out heavy metal with their 1970 debut. Creedence Clearwater Revival delivered one of their strongest records the same year. David Bowie introduced the Ziggy Stardust persona in 1972. Pink Floyd released The Dark Side of the Moon in 1973, a record so culturally fixed it spent more than 18 consecutive years on the charts. And Led Zeppelin’s run speaks for itself, with four massive albums in five years, culminating in crowds of more than 70,000 packing stadiums to see them by 1977.

Rock’s Dominance Through the Decade

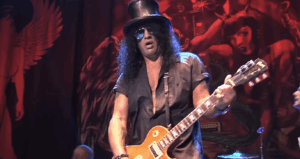

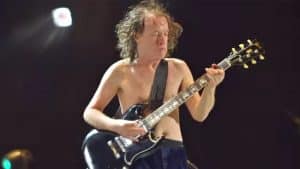

However, the decade gets retold today, rock controlled the mainstream from the start of the ’70s to its close. FM radio leaned heavily toward rock-driven formats, and touring became a spectacle the world hadn’t seen before. Acts like Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, and Pink Floyd transformed concerts into full-scale events with stage production, lighting, and sound systems that dwarfed anything offered in earlier decades.

Album sales told the same story. Rock LPs didn’t just sell well — they defined what the “album era” would become. Bands pushed creative concepts, experimented with long-form songwriting, and treated albums as complete artistic statements. This shift helped turn records into cultural milestones rather than disposable hits, a trend that carried deep into the ’80s before the rise of CDs and digital formats rewired the industry again.

Even as disco’s glittering rise began to take over headlines late in the decade, rock’s presence never retreated. In 1977, the same year Saturday Night Fever landed, Fleetwood Mac released Rumours, one of the best-selling albums of all time. Pink Floyd followed in 1979 with The Wall. Rock continued to headline festivals and pack venues. The supposed clash between genres was never a battle over dominance — it was a collision of two massive forces temporarily sharing the same moment.

Disco’s Flash, Backlash, and the Misleading Myth

Disco’s rise was undeniably fast, and its imagery left a lasting imprint. What began in New York’s club culture — shaped by DJs blending imported European dance records — grew into a global phenomenon within just a few years. Artists like Donna Summer and Diana Ross helped push disco into the charts, and the Bee Gees cemented it with songs that filled dance floors worldwide.

The problem is that disco’s explosion late in the decade tends to overshadow everything else in retrospect. Because it was visually distinctive, culturally provocative, and tied heavily to nightlife and identity politics, it stuck in people’s memories with unusual intensity. And its dramatic fall — punctuated by 1979’s infamous “Disco Demolition Night” — only strengthened the illusion that it had been the defining force of the entire decade.

In truth, disco spent only a short time at the top, while rock powered the ’70s from beginning to end. Rock shaped the charts, drove album sales, and filled the biggest venues. Disco added color, controversy, style, and one unforgettable soundtrack, but it never erased rock’s overwhelming presence. The modern belief that the ’70s were “the disco decade” has more to do with visual memory than musical reality. The decade, in all its texture, belonged to rock — and it always did.