Exploring Frank Zappa’s Exclusive List Of 10 Favorite Songs

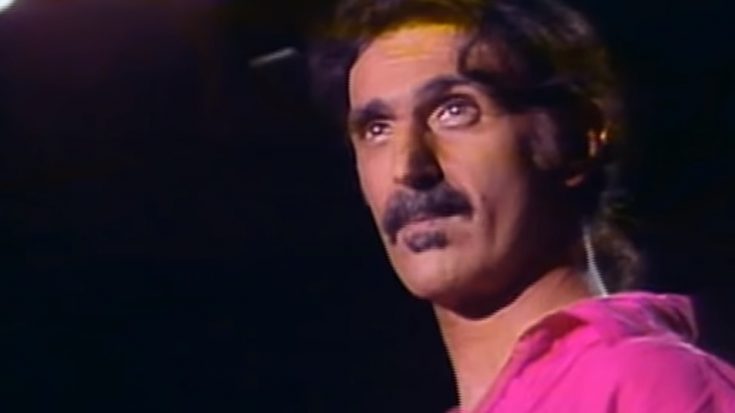

Frank Zappa live in 1984 - F.Q.C. RÉCORDS FQC-RECORDS / Youtube

The phrase “genre-defying” is spoken about a lot, in part because there are people who are quite picky about classification, and staying away from it is a safe method to move across the classified terrain. Still, few musicians meet the description quite like Frank Zappa. His music celebrates individuality, reflecting his own nature.

Similarly, his music is more like classical music than standard rock ‘n’ roll, even with its instruments. When Zappa was a high school drummer, he was first influenced by modern classical music with a lot of percussion.

Later, he picked up a guitar and started playing doo-wop. Zappa was very pleased with the peculiar combination that he created by combining simple blues pop with complex orchestration.

If the odd combination wasn’t enough, the varied assortment merely shows a portion of the story, or as Zappa put it, “exactly 50%”. The following are the tracks that the mustached musician selected as faves on Castaway’s Choice, an American radio program that copied the classic BBC program Desert Island Discs, back in 1989.

“Octandre” by Edgard Varèse

Edgard Varèse’s 1923 composition Octandre was released by J. Curwen & Sons in London in 1924 and it was dedicated to pianist E. Schmitz Robert.

Comprising three movements—Assez lent, Très vif et nerveux, Grave–Animé et jubilatoire—Octandre is orchestrated for 1 piccolo/flute, 1 oboe, 1 B♭ clarinet/E♭ clarinet, 1 horn, 1 bassoon, 1 trumpet (in C), 1 trombone, and 1 double bass.

The pieces by Varèse that highlight percussion, the combination of electronics and traditional instruments, and Poème électronique, an entirely electronic work made for a three-track tape and intended for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, are his most well-known works.

“The Royal March from L’Histoire Du Soldat” by Igor Stravinsky

Histoire du soldat, originally titled Tale of the Soldier, is a 1918 theatrical work intended for three actors, one or more dancers, and a septet of instruments to be “read, played, and danced (lue, jouée et dansée)”. Influential Russian composer Igor Stravinsky wrote the music, and Swiss novelist Charles Ferdinand Ramuz wrote the French libretto. The Russian story The Runaway Soldier and the Devil, which can be found in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection, served as the basis for the joint idea of the two pieces.

The dark Faustian tale follows the travels of Joseph, a deserting soldier, and his ultimate ownership by the Devil. Joseph’s violin takes on a dual meaning, representing the Devil’s crafty influence and his own soul.

Zappa’s favorite “Royal March” is in the second part, where the soldier makes his way to the palace to check on the king’s sick daughter. While rooted in an ancient Russian folk tale, the music diverges significantly from Russian traditionalism, serving as a universal lesson transcending cultures and eras.

“The Rite Of Spring” by Igor Stravinsky

Another Stravinsky composition found its way to Zappa’s playlist, and it’s the ballet and orchestral concert piece titled The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps). Written specifically for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes company’s 1913 Paris season, it included stage designs and costumes by Nicholas Roerich alongside unique choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky.

A sensation was created when the music and choreography were initially presented on May 29, 1913, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées due to its avant-garde style. The first-night reaction has been referred to by many as a “riot” or “near-riot”, yet this wording did not exist until evaluations of subsequent performances in 1924, more than ten years later.

In his book Conversations, 45 years after the ballet’s debut in 1913, Igor Stravinsky recounted, “The Rite of Spring came to me while I was still composing Firebird. I had dreamed of a scene of pagan ritual in which a chosen sacrificial virgin danced herself to death.”

“The first movement from Third Piano Concerto” by Béla Bartók

The Third Piano Concerto by Béla Bartók in E major, Sz. 119, BB 127, is an orchestral and keyboard composition. Written in 1945, in the final months of Bartók’s life, it was a surprise birthday present for Ditta Pásztory-Bartók, his second wife. Zappa called the first movement of this iconic composition “one of the most beautiful melodies ever written”.

The concerto, which consists of three movements (Allegretto, Adagio religioso, and Allegro vivace), usually lasts between twenty-three and twenty-seven minutes when performed in its entirety. Primarily in E major, the opening movement features a unique Hungarian “folk theme”, evocative of a verbunkos dance from the 19th century.

In the latter months of his life, Bartók composed the Third Piano Concerto while battling terminal disease and financial hardships. The resulting piece of music can be seen as a bright musical “farewell” at a time when the artist was facing personal tragedy and darkness.

“Stolen Moments” by Oliver Nelson

The jazz standard “Stolen Moments” was composed by Oliver Nelson. The song acquired wider exposure after being covered on Nelson’s 1961 album, The Blues and the Abstract Truth.” Mark Murphy added words to the music in his 1978 interpretation. Although it has a 16-bar structure, the solos follow a standard minor blues framework.

The song, originally named “The Stolen Moment”, first appeared on Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis’s 1960 album Trane Whistle, which Nelson wrote and co-arranged most of the music for. At first, it wasn’t emphasized as anything special; the cover notes just gave Bobby Bryant credit for the trumpet solo and referenced Eric Dolphy’s bass clarinet in passing in the last remarks.

But according to Bill Kirchner’s liner notes for Eric Dolphy: The Complete Prestige Recordings, Dolphy actually contributed as the second alto behind Nelson, despite the credits mistakenly attributing Dolphy to George Barrow’s baritone saxophone.

“Three Hours Past Midnight” by Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson

Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson’s “Three Hours Past Midnight” was the track that is said to have inspired Frank Zappa to be a guitarist, and you can certainly see the shadow of Watson’s aggressive style in Zappa’s music. The vocalist of The Mothers of Invention had even once said that if he had to single out favorite one record, his preference would be this 1965 track from Watson.

Born John Watson Jr., Johnny “Guitar” Watson was an energetic performer and electric guitarist who was influenced by T-Bone Walker’s sound. Throughout the course of four decades, Watson recorded songs in the genres of soul, funk, and rhythm and blues.

Zappa managed to establish a connection with his musical idol, and Watson contributed to the albums of the eccentric musician, including One Size Fits All (1975), Them or Us (1984), Thing-Fish (1984), and Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention (1985).

“Can I Come Over Tonight?” by The Velours

“Can I Come Over Tonight?” is one of the few minor hits of The Velours, an American R&B vocal group that relocated to the UK and changed their name to The Fantastics. This track, written by tenor Donald Haywoode, reached number 83 on the Billboard pop chart in 1957.

Originating in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, The Velours are particularly beloved among fans of doo-wop and early R&B. They are renowned for their versatility and skill on the vocals, having performed a wide variety of rock, pop, and ballads.

The group disbanded in 1961 after achieving little success in the late 50s, but Haywoode and two other tenor members Jerome Ramos and John Cheatdom decided to reform and toured the UK. They achieved better results this time and stayed in Britain as The Fantastics.

“Bagatelles for String Quartet” by Anton Webern

Anton Webern was an Austrian composer and conductor. Renowned for his radical approach, his music stood out for its concise nature and unwavering commitment to the then-novel atonal and twelve-tone techniques. This dedication to innovation reflected a disciplined style reminiscent of the Franco-Flemish School.

Webern’s string quartet compositions, Six Bagatelles, Op. 9 (1911–13), represent a turning point in the evolution of atonal compositional methods. They also marked an important turning point in the composer’s career as he worked to bring his mentor Arnold Schoenberg’s ideas to life and establish himself as a unique and innovative composer. For many years Webern had respected Schoenberg as a person and as an artist.

Usually, the Six Bagatelles take about five minutes to perform. Op. 9 differs significantly from Webern’s previous quartet, Op. 5, in that the former does not have movements made up of sections and contrasts.

“Symphony, Opus 21” by Anton Webern

Symphony, Opus 21 is another work by Anton Webern that Zappa loved. In 1950, conductor René Leibowitz, along with the Pro Arte Quartet and the Paris Chamber Orchestra, recorded a version of this composition.

Released on the Dial label, the album included not only Webern’s Symphony, Opus 21 but also his Five Movements for String Quartet and Six Bagatelles for String Quartet. The album’s artwork was crafted by renowned artist David Stone Martin.

In his book, The Real Frank Zappa Book, Zappa shared his adoration for Weber and his works, as well as the Leibowitz album: “The other composer who filled me with awe — I couldn’t believe that anybody would write music like that — was Anton Webern. I heard an early recording on the Dial label with a cover by an artist named David Stone Martin — it had one or two of Webern’s string quartets, and his Symphony op. 21 on the other side.”

“Piano Concerto in G” by Maurice Ravel

The G major Piano Concerto by Maurice Ravel was composed between 1929 and 1931. With three movements, the concerto has a little more than twenty minutes of playing time overall. Ravel explained that he was inspired by the musical genres of Mozart and Saint-Saëns and that his goal in writing this work was not so much profundity as amusement. Additionally, the composition draws inspiration from Basque traditional music and jazz.

Zappa’s 1966 debut album Freak Out! features a list of inspirations that includes Ravel under a heading titled “These People Have Contributed Materially In Many Ways To Make Our Music What It Is. Please Do Not Hold It Against Them.”

The avant-garde musician also performed a five-minute version of Ravel’s 15-minute Boléro during concerts in the late 1980s. He included this rendition on The Greatest Band You’ve Never Heard Of, but copyright troubles forced it out of the European releases.