10 Classic-Rock Bands Who Embraced Hip-Hop — and Changed the Game

via NEA ZIXNH / YouTube

Back when musical boundaries were clearly drawn, rock and hip-hop seemed like they came from two different planets. Rock ruled the airwaves for decades, shaping generations with its guitars, rebellion, and swagger. But by the late 1970s, a new sound began to pulse from the city streets — one that spoke through rhythm, poetry, and turntables rather than guitars and amps. Hip-hop wasn’t just a genre; it was a movement, and its rise signaled a shift in how music could be created, shared, and experienced.

At the heart of hip-hop was a simple but radical idea: take something old and make it new. DJs and MCs began cutting, looping, and sampling records — transforming familiar rock riffs and funk breaks into something electrifyingly different. It wasn’t long before those in the rock world took notice. Artists who had once dominated arenas were suddenly inspired by what was happening in urban neighborhoods, where experimentation was the rule, not the exception.

Some rock acts were quick to see the potential in this cultural collision, while others stumbled into it by chance. Whether through deliberate collaboration or unexpected crossover moments, these classic-rock icons found themselves part of hip-hop’s expanding universe. What followed was a creative exchange that reshaped both genres — proving that music’s most powerful moments often come from breaking the rules.

The Clash

When the Clash arrived in late-’70s New York, they found themselves at the crossroads of a musical revolution. The city’s emerging hip-hop culture — raw, rhythmic, and fiercely independent — struck a chord with the English punk rebels. Just as punk was born from frustration and rebellion, so was hip-hop. The Clash immediately saw the connection, recognizing rap as the new voice of the streets.

Rather than staying confined to their punk bubble, the band opened their arms to this new sound. They began inviting early rap pioneers like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, the Treacherous Three, and ESG to share their concert stages — a daring move at the time. Their 1980 track “The Magnificent Seven” fused disco grooves with spoken-word rhythm, directly inspired by the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight.” The single’s B-side, “The Magnificent Dance,” even became a surprise favorite on hip-hop radio stations.

This unlikely fusion earned the Clash respect far beyond the punk scene. Rap icons like Chuck D later credited the band for their influence, noting how the Clash’s bold, socially charged lyrics set a blueprint for groups like Public Enemy. In bridging punk’s aggression with hip-hop’s urgency, the Clash helped shape a cultural handshake between two of music’s most defiant movements.

Blondie

By the late ’70s, Blondie had already conquered New York’s underground with their sleek blend of punk, disco, and new wave. But Debbie Harry and guitarist Chris Stein were never content to stay in one lane. Immersed in the city’s art and club scenes, they found themselves mingling with hip-hop’s earliest innovators — Fab 5 Freddy, Grandmaster Flash, and others who were busy turning turntables into instruments. Blondie didn’t just observe the movement; they embraced it.

Their 1981 hit “Rapture” became the first No. 1 single in the U.S. to feature rapping — a cultural milestone that many fans didn’t see coming. The track playfully name-dropped Fab 5 Freddy and Flash, introducing millions of mainstream listeners to hip-hop for the first time. Its title itself was a wink to “rap-ture,” signaling the duo’s deep respect for the art form.

Years later, Harry reflected on how many rappers told her that “Rapture” was their first exposure to hip-hop. Artists from Wu-Tang Clan to Mobb Deep credited the song for sparking their early curiosity. Blondie’s willingness to take a creative leap turned what could have been a novelty experiment into a defining crossover moment — one that helped open radio’s doors for rap music.

Aerosmith

In 1986, Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” became the song that broke down the wall between rock and rap. Originally recorded in 1975, it was reimagined by Run-D.M.C. and producer Rick Rubin, who saw in the song’s swagger a perfect bridge between the two worlds. Joe Perry and Steven Tyler weren’t sure what to expect when approached for the collaboration, but curiosity — and good timing — won them over.

Perry’s young son happened to be blasting Run-D.M.C. records at home, giving the guitarist an early appreciation for their sound. When Rubin called about reworking “Walk This Way,” Perry was already sold. Tyler’s powerhouse vocals collided with Run-D.M.C.’s sharp delivery, creating a track that sounded like nothing else on the radio.

The collaboration revitalized Aerosmith’s career and gave hip-hop its first major crossover hit on MTV. That music video — with the two acts literally breaking down a wall between their rehearsal rooms — became an iconic symbol of musical unity. “Walk This Way” didn’t just merge genres; it redefined what mainstream music could sound like in the late ’80s.

Led Zeppelin

Led Zeppelin never planned to join the hip-hop revolution, but their music became part of its foundation. When the Beastie Boys released Licensed to Ill in 1986, their Rick Rubin-produced debut became the first rap album to top the Billboard chart — and it was built on Led Zeppelin samples. The band’s thunderous beats and riffs, especially John Bonham’s explosive drumming from “When the Levee Breaks,” became sonic gold for hip-hop producers.

The Beastie Boys didn’t ask permission before looping Zeppelin’s material, but the surviving members weren’t angry — they were impressed. Robert Plant, in particular, admired how creatively they reimagined the music. Instead of clinging to the past, he took inspiration from the Beasties and later used Zeppelin samples in his own solo hit, “Tall Cool One.”

Plant’s embrace of sampling showed just how far rock’s influence had traveled. What began as an unintentional tribute evolved into a full-circle exchange between generations. Zeppelin’s sound became part of hip-hop’s DNA, influencing everyone from the Beastie Boys to Eminem. In a way, the band’s monumental grooves found a second life — louder, heavier, and even more rebellious.

Anthrax

By the late ’80s, Anthrax had already built a reputation as one of metal’s most fearless bands. Guitarist Scott Ian saw parallels between his world and that of Public Enemy — both thrived on attitude, speed, and unapologetic energy. When Chuck D and Flavor Flav name-dropped Anthrax on “Bring the Noise,” Ian decided to take the connection a step further.

The 1991 remake of “Bring the Noise” combined Public Enemy’s fiery verses with Anthrax’s blistering guitar work, creating one of the earliest and most successful rap-metal hybrids. The collaboration wasn’t just a studio experiment — it sparked a real friendship between the two groups. Together, they took the song on tour, thrilling both headbangers and hip-hop fans across the U.S.

That tour broke cultural barriers and set the stage for future acts like Rage Against the Machine and Linkin Park. More than a novelty, Anthrax and Public Enemy’s collaboration proved that aggression and rhythm could coexist beautifully. It was a loud, defiant reminder that when genres collide, innovation follows.

The Police

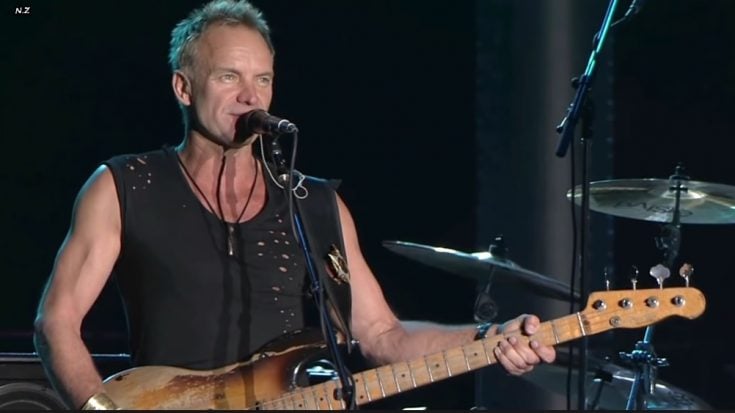

When Puff Daddy released “I’ll Be Missing You” in 1997, few could have predicted that it would tie one of rock’s most haunting melodies to hip-hop’s emotional storytelling. Built on the bones of the Police’s “Every Breath You Take,” the tribute to the late Notorious B.I.G. became a worldwide hit — and a legal headache. Sting, the sole credited writer of the song, pursued the matter in court and eventually received full royalties for the track. What began as a copyright battle slowly turned into something far more unexpected.

Instead of distancing himself from hip-hop, Sting chose to embrace it. That same year, he joined Puff Daddy onstage at the MTV Video Music Awards to perform the song live — a symbolic peace offering that marked a rare moment of unity between two generations of popular music. The performance helped redefine how artists from different worlds could coexist, turning what started as a dispute into a statement about shared creativity.

Years later, despite controversies surrounding Diddy, Sting maintained that “Every Breath You Take” still held its magic. The experience even encouraged him to continue experimenting, leading to collaborations with Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre on “Another Part of Me,” which playfully revisited the Police’s “Message in a Bottle.” From litigation to collaboration, the Police’s brush with hip-hop proved that music — even when borrowed — can bridge divides.

ZZ Top

ZZ Top’s blues-soaked riffs might seem far removed from hip-hop’s urban rhythms, but the Texas trio found surprising common ground in the studio. During sessions for their 2012 album La Futura, the band decided to rework “25 Lighters,” a Houston hip-hop hit originally released in 1989 by DJ DMD. Billy Gibbons explained that while waiting out studio renovations, they ended up hanging out with local rap producers, swapping ideas and trading sounds.

The collaboration wasn’t forced — it was born out of curiosity and respect. “We were comparing notes and exchanging ideas,” Gibbons later said. “They were showing us beats, and I was showing them guitar stuff.” The result was “I Gotsta Get Paid,” a gritty, swaggering reinvention that blended hip-hop’s rhythmic confidence with ZZ Top’s signature southern crunch.

Released as the album’s lead single, the song became a late-career highlight for the band, proving that even rock’s most old-school icons could adapt without losing their identity. ZZ Top didn’t just cover a rap track — they made it their own, bridging the dusty Texas roadhouse with the pulse of Houston’s hip-hop underground.

Johnny Rotten

After the Sex Pistols imploded, John Lydon — forever known as Johnny Rotten — wasn’t about to fade quietly into nostalgia. Always chasing what was new and disruptive, he turned his attention to hip-hop’s early rise. In 1984, Lydon teamed up with Afrika Bambaataa and his Time Zone project for “World Destruction,” a song that boldly fused punk aggression with hip-hop rhythm, years before the mainstream caught on.

The collaboration came naturally. Lydon admired Bambaataa’s fearless mixing of funk, rock, and electronic music — and saw parallels between that boundary-breaking spirit and punk’s own rebellion. “He loves all music,” Lydon said in a later interview. “He’d do these amazing crossovers, and I’d always be there on the dance floor.” The two artists bonded over their shared desire to shake up expectations, creating something raw, political, and ahead of its time.

“World Destruction” may not have topped the charts, but its influence rippled through music history. It laid the groundwork for later rap-rock hybrids and showed that punk’s confrontational energy could thrive in hip-hop’s world. Long before collaborations like “Walk This Way” or “Bring the Noise,” Lydon and Bambaataa proved that rebellion has no genre.

Billy Squier

Billy Squier might not be the first name that comes to mind when you think of hip-hop, yet his songs are everywhere in it. In the 1980s, as his chart-topping streak began to fade, something unexpected happened — rappers started sampling his work. His thunderous drums and infectious grooves made perfect material for producers seeking punch and rhythm, turning Squier into one of the most sampled rockers in hip-hop history.

From Run-D.M.C. and Grandmaster Flash to Eminem, Jay-Z, Kanye West, Nas, and A Tribe Called Quest, Squier’s catalog became a treasure trove for beatmakers. Tracks like “The Big Beat” and “Lonely Is the Night” formed the backbone of countless hip-hop classics. What was once arena rock found new life in the hands of MCs and DJs who transformed his riffs into street anthems.

Even rap legend Big Daddy Kane credited Squier as a foundational influence, saying he “gave the B-boys and B-girls a track to dance to.” It’s a legacy Squier never saw coming — a reminder that sometimes, influence doesn’t come from reinvention but from rediscovery. Through hip-hop, Billy Squier’s music reached audiences that rock radio never could.

Kerry King (Slayer)

When Slayer’s Kerry King stepped into a hip-hop studio in the mid-’80s, it wasn’t a grand artistic statement — it was a gig. Working down the hall from the Beastie Boys during recording sessions for Licensed to Ill, King was asked by producer Rick Rubin to play guitar on a track called “No Sleep Till Brooklyn.” At first, he hesitated. The collaboration seemed odd, and the paycheck — a few hundred bucks — was modest. But he went for it anyway, unaware he was about to make rap-rock history.

King’s roaring guitar solo became one of the defining moments on the Beastie Boys’ breakout album. He even appeared in the music video, where he was supposed to be knocked offstage by a man in a gorilla suit — an idea he vetoed in favor of a scene where he takes a swing at the primate instead. The result was pure chaos, fitting perfectly with both Slayer’s intensity and the Beasties’ humor.

Looking back, King called it a “happy accident.” What started as a simple session gig turned into one of rap’s earliest flirtations with heavy metal. “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” not only helped launch the Beastie Boys to superstardom but also gave Slayer unexpected exposure to MTV’s massive audience. For a metal guitarist just trying to make rent, it was a career twist that rocked both worlds.